A story from inside WP3

In our previous article, we introduced how the MOBILES project studies soil microbial communities to understand how pollution affects them and how these microorganisms may support soil recovery. We explained the principles of metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, and the role of bioinformatics in analysing complex microbial data.

In this follow-up article, we take the next step: how the soil samples themselves are collected, transported, and prepared before they ever reach a sequencer. While sequencing and data analysis reveal what microbes are doing, the quality of those results depends entirely on how each sample begins its journey. Today, we invite you behind the scenes to follow the journey of a single soil sample as it moves from the landscape to the laboratory, eventually becoming data that help us understand how pollution shapes European soils.

Before any soil is collected, the project team carefully chooses sampling sites across Europe. These areas represent environments affected by different forms of pollution: microplastics, heavy metals, hormones, and antibiotics. To ensure reproducibility, each location is precisely mapped using GPS tools and easily recognisable reference points are recorded for future visits. No special permits are required—the areas are public or already used in partner research—but accuracy matters. Each placed dot on the GPS map becomes a tiny anchor for upcoming soil collections.

The goal is simple: capture the soil exactly as it is, without altering the microbial life inside it.

In the previous article, we described that samples are taken from a 0–20 cm soil layer—the zone with the highest microbial activity. But how that soil is collected is equally important and often more challenging than it sounds. Sampling must avoid extreme weather conditions. It cannot take place after prolonged drought, nor after frost or flooding, because microbes behave differently under these environmental stresses. Plant material, roots, stones, and fauna are removed to avoid altering microbial composition

A single scoop does not tell the whole story, so the researchers repeat the process again and again—at least ten times across a small area—and pool all the soil together. This approach ensures that the resulting sample reflects real soil conditions rather than a single micro-spot.

Microbes never sleep. Once soil

is removed from the ground, they begin to change. Some thrive in the new

conditions, others decline. The goal now is to freeze this moment in time as

fast as possible. In the field, the sample is

cooled immediately to about 4°C. During the transport to the central laboratory,

it travels on dry ice. Once at the laboratory, it is stored in a freezer at

–80°C until researchers are ready to begin.

For DNA, this cooling preserves

the list of microbial species present.

For RNA, it preserves information of the activity of those species at the

precise moment of sampling. Without strict temperature control, this fragile

information would be altered or disappear completely.

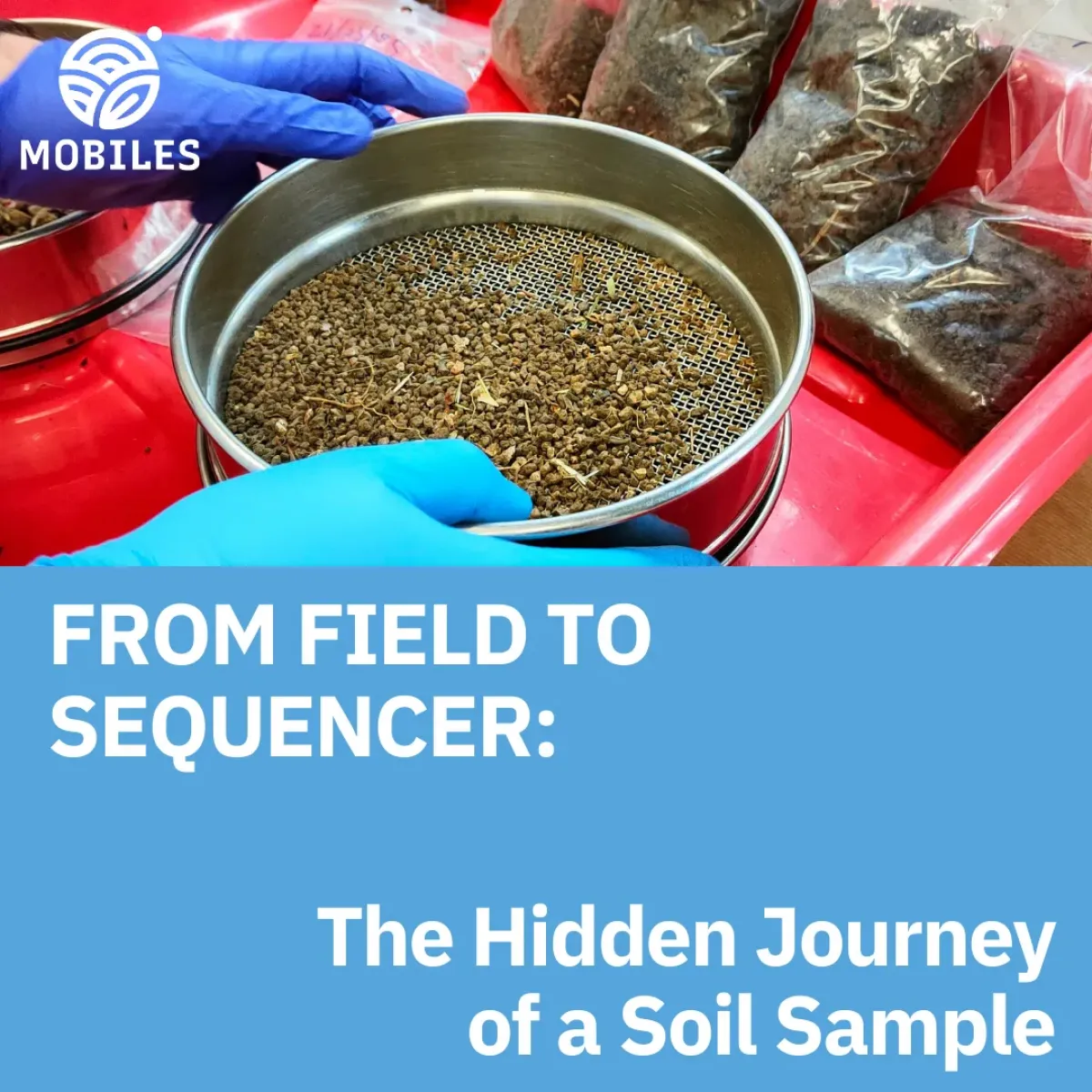

At the ISSPC laboratory, each

sample undergoes a careful preparation process. The labelled bags are opened and

the soil poured onto trays to remove leftover stones or root fragments. Clumps

are gently broken apart and the soil is passed through a fine 2 mm sieve. This

step, while simple, is key: it creates a uniform material that can be compared

across countries and contaminants. If the soil is too wet, it is air-dried

under a soft flow of air, not heated, not forced, just allowed to return to a

state suitable for analysis.

Each processed sample is split into three technical replicates, ensuring that

results are repeatable.

Each replicate is placed in a container

depending on the type of subsequent analysis (chemical characterisation,

DNA/RNA extraction, or long-term storage).

Now the soil is ready to reveal

its secrets. The laboratory isolates both DNA

and RNA from each soil sample. Quality and concentration checks ensure that the

extracted material is suitable for sequencing. If any issues arise, for example unusually low RNA levels, the extraction is repeated to maintain high data

quality across all countries.

Half of the extracted material

becomes part of a long-term reference collection.

The other half moves on to sequencing.

Once sequencing is complete, scientists will reconstruct microbial communities, identify signatures of pollution, and begin to understand which organisms may be key to helping soils recover.

In microbiome research, every

detail counts—from the moment the soil is touched, to the conditions during

transport, to the final extraction of nucleic acids. Without consistent and

rigorous sampling procedures, sequencing results could reflect handling errors

rather than real environmental differences.

By following a harmonised

protocol across the consortium, MOBILES ensures that its metagenomic data rests

on a solid and trustworthy foundation. This careful behind-the-scenes process

supports all later analyses, including the development of microbial indicators,

pollutant-response studies, and strategies for soil rehabilitation.